advertisement

World Kiswahili Language Day: Call To Expand Africa’s Digital Linguistic Presence?

Infolge of the previous over the past few weeks, Kenya has seen a rapid rate of civic tech development at speeds never experienced before. As the beloved Gen Z took to the streets to express their displeasure with the Kenya Finance Bill 2024, a digital movement was coming together on the sidelines to empower even more Kenyans with the why behind the protests.

In a matter of days, the Kenya Finance Bill 2024 was chunked into bite sizes and explainers hurriedly provided in short video format on TikTok, X and Instagram. These explainer videos then made their way to WhatsApp groups, and while the trend started in English, and was mainly targeted at Gen Z, an urgent need to speak to parents and Gen Z in the rural areas arose. We saw videos being done in over 10 local languages and spread out across all social media platforms. And mostly voluntary. In contrast, an LLM (Large Language Model) for the Finance Bill was released and made available in English and Kiswahili.

As we observe the growth of digital activism, it highlights the stark gap of an all-inclusive AI ecosystem for Africa. Our observations were two-fold; African languages are still very oral, and critically underrepresented in the realm of AI, as observed in the LLMs that could only do English and Kiswahili, and second, there is a need for a different approach to the creation of the language datasets – as observed in the viral explainer videos.

advertisement

As fate would have it, Kenya, for the first time, hosted the World Kiswahili Language Day celebrations from 5-7 July, featuring a series of events, key among them being Usiku wa Mswahili. World Kiswahili Language Day, observed annually on July 7, was established by the General Conference of the United Nations Educational and Scientific Organization (UNESCO) in November 2021, during its 41st session. The proclamation of the day was in recognition of the role played by the language in cultural preservation, awareness creation, expression and social participation. This proclamation was not without merit, given the prominence of the language. Kiswahili is the most widely spoken language in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 200 million speakers spanning more than 14 countries. Moreover, it is one of the 10 most spoken languages globally. It is the official working language of several organisations: East African Community (EAC), Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU).

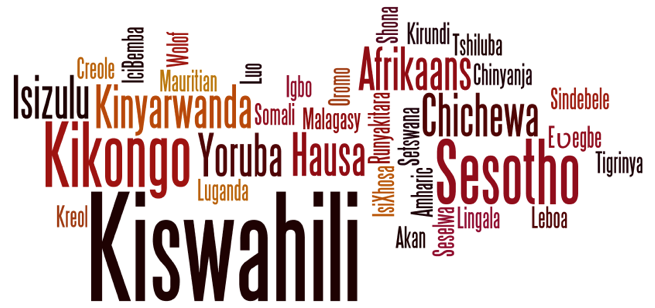

Even with this reach, Kiswahili’s digital presence is limited; as such it is considered a low-resource language. Consequently, the availability of text and speech data that is available in a digitised format is limited for Kiswahili. Many African languages suffer the same fate i.e. either a limited digital presence, or none at all. Africa is considered one of the most linguistically diverse continents in the world, with the number of spoken languages estimated to exceed 2,000.

advertisement

The limited availability or lack thereof of data in a digitised form is exclusionary in many ways, especially in this era of the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution, which has seen a proliferation of language applications (text-to-speech, machine translation), virtual assistants such as Alexa and Siri, and tools (ChatGPT, Llama2 and Mistral AI). The development of such tools and applications essentially entails the following: 1) collecting of language data; 2) tool development i.e. training models with collected data; and, 3) deployment of developed tools. Given the dearth of African language datasets, the ability of AI researchers and Natural Language Practitioners (NLP) practitioners to leverage AI techniques to build African language tools is severely limited. This limited availability intensifies the digital divide, mutes the digital presence of millions of Africans and limits economic opportunities.

advertisement

Given the centrality of datasets to the innovation of bespoke African models and AI tools, the creation and expansion of language datasets remains imperative. The creation or expansion of language datasets, especially within the context of African languages, is a mammoth task due to the diversity of languages exhibited on the continent. Further, this task becomes explosive when dialects within languages are taken into account. With limited resources (time, talent and finances), the need for an efficient data creation/expansion pathway becomes pertinent. Indexes constitute an important barometer in the realization of efficiency-oriented efforts. Already, indexes such as the Government AI Readiness Index 2023 are proving to be useful tools in assessing the extent to which countries are prepared to integrate AI within the public sector. A similar index geared towards languages such as the Global Language Readiness Index would prove extremely useful to priority setting.

Through collaborative efforts across the spectrum of AI and Natural Language Processing practitioners, such an index would outline critical pillars and indicators for gauging language readiness. Through such an index, indicators measuring the extent to which a given African language is machine-ready concerning text and speech data will prove useful in several ways: identifying gaps in getting African languages AI-ready, identifying priority areas for data collection/expansion efforts and designing efficient language data collection and expansion strategies. An index affords a systematic efficient approach for the creation/expansion of African language datasets, which in turn will accelerate the innovation of African language tools and applications. Such advancements will ensure that speakers of African languages can access language tools in their tongue, leading to a host of benefits; for instance, narrowing of the digital divide, integration of African voices and accelerated economic growth.

As we continue witnessing the unfolding digital civic engagement spilling across Africa, it is important to ensure that the tools being created are inclusive for all Africans.

This article was written by Kavengi Kitonga and Dr Shikoh Gitau