advertisement

Wireless charging explained: What is it and how does it work?

Wireless charging has been around since the late 19th century, when electricity pioneer Nikola Tesla demonstrated magnetic resonant coupling –…

Wireless charging has been around since the late 19th century, when electricity pioneer Nikola Tesla demonstrated magnetic resonant coupling – the ability to transmit electricity through the air by creating a magnetic field between two circuits, a transmitter and a receiver.

But for about 100 years it was a technology without many practical applications, except, perhaps, for a few electric toothbrush models.

Today, there are nearly a half dozen wireless charging technologies in use, all aimed at cutting cables to everything from smartphones and laptops to kitchen appliances and cars.

advertisement

Wireless charging is making inroads in the healthcare, automotive and manufacturing industries because it offers the promise of increased mobility and advances that could allow tiny internet of things (IoT) devices to get power many feet away from a charger.

OSSIA

OSSIAThe most popular wireless technologies now in use rely on an electromagnetic field between a two copper coils, which greatly limits the distance between a device and a charging pad. That’s the type of charging Apple has incorporated into the iPhone 8 and the iPhone X.

How wireless charging works

Broadly speaking, there are three types of wireless charging, according to David Green, a research manager with IHS Markit. There are charging pads that use tightly-coupled electromagnetic inductive or non-radiative charging; charging bowls or through-surface type chargers that use loosely-coupled or radiative electromagnetic resonant charging that can transmit a charge a few centimeters; and uncoupled radio frequency (RF) wireless charging that allows a trickle charging capability at distances of many feet.

advertisement

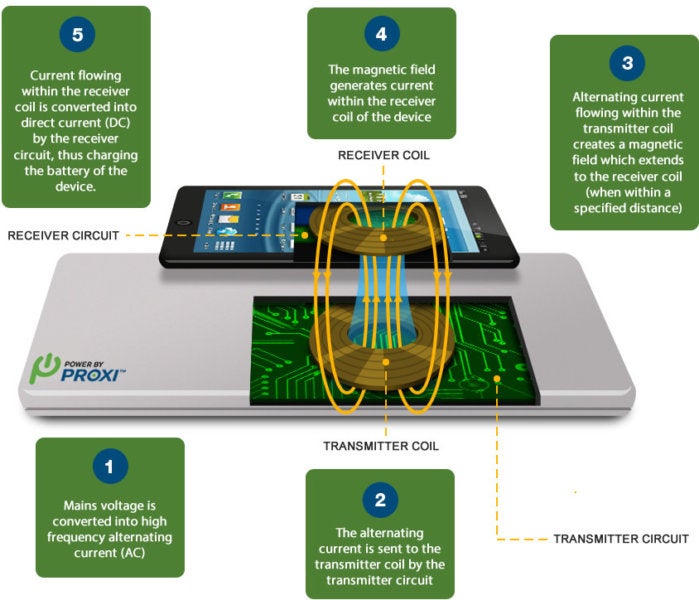

Both tightly coupled inductive and loosely-coupled resonant charging operate on the same principle of physics: a time-varying magnetic field induces a current in a closed loop of wire.

IKEA

IKEAIt works like this: A magnetic loop antenna (copper coil) is used to create an oscillating magnetic field, which can create a current in one or more receiver antennas. If the appropriate capacitance is added so that the loops resonate at the same frequency, the amount of induced current in the receivers increases. This is resonant inductive charging or magnetic resonance; it enables power transmission at greater distances between transmitter and receiver and increases efficiency. Coil size also affects the distance of power transfer. The bigger the coil, or the more coils there are, the greater the distance a charge can travel.

In the case of smartphone wireless charging pads, for example, the copper coils are only a few inches in diameter, severely limiting the distance over which power can travel efficiently.

advertisement

But when the coils are larger, more energy can be transferred wirelessly. That’s the tactic WiTricity, a company formed from research at MIT a decade ago, has helped pioneer. It licenses loosely-coupled resonant technology for everything from automobiles and wind turbines to robotics.

In 2007, MIT physics professor Marin Soljačić proved he could transfer electricity at a distance of two meters; at the time, the power transfer was only 40% efficient at that distance, meaning 60% of the power was lost in translation. Soljačić started WiTricity later that year to commercialize the technology, and its power-transfer efficiency has greatly increased since then.

In WiTricity’s car charging system, large copper coils – over 25 centimeters in diameter for the receivers – allow for efficient power transfer over distances up to 25 centimeters. The use of resonance enables high levels of power to be transmitted (up to 11kW) and high efficiency (greater than 92% end-to-end), according to WiTricity CTO Morris Kesler. WiTricity also adds capacitors to the conducting loop, which boosts the amount of energy that can be captured and used to charge a battery.

The system isn’t just for cars: Last year, Japan-based robotics manufacturer Daihen Corp. began shipping a wireless power transfer system based on WiTricity’s technology for automatic guided vehicles (AGVs). AGVs equipped with Daihen’s D-Broad wireless charging system can simply pull up to a charging area to power up and then go about their warehouse duties.

While charging at a distance has big potential, the public face of wireless charging has until now remained with charging pads.

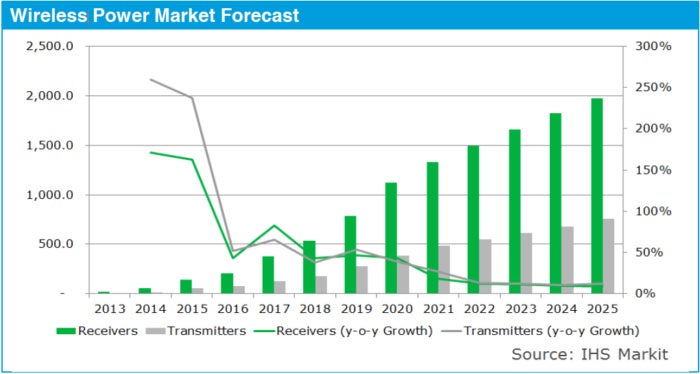

IHS MARKIT

IHS MARKIT“In terms of progress and industry readiness, charging pads have been shipping in volume since 2015; charging bowls/through-surface type are really just launching this year; and charging across a room is probably still at least a year away from commercial high-volume reality–- although the new Energous products show this method working over very short range right now, e.g., a couple of centimeters,” Green said.

Just over 200 million wireless charging-enabled devices shipped in 2016, with almost all of them using some form of inductive (charging pad) type design.

In September, Apple finally chose a side after lagging behind other handset manufacturers for years by embracing WPC’s Qi standard, the same that Samsung and other Android smartphone makers have been using for at least two years.

The first class of mobile device wireless chargers emerged a six or so years ago; they used tightly coupled or inductive charging, which requires users to place a smartphone in an exact position on a pad for it to charge.

“In my mind, lining it up exactly to charge doesn’t save you a lot of effort from just plugging it in,” said Benjamin Freas, principal analyst for Navigant Research.

While early adopters and techies bought into inductive charging, others did not, Freas said.

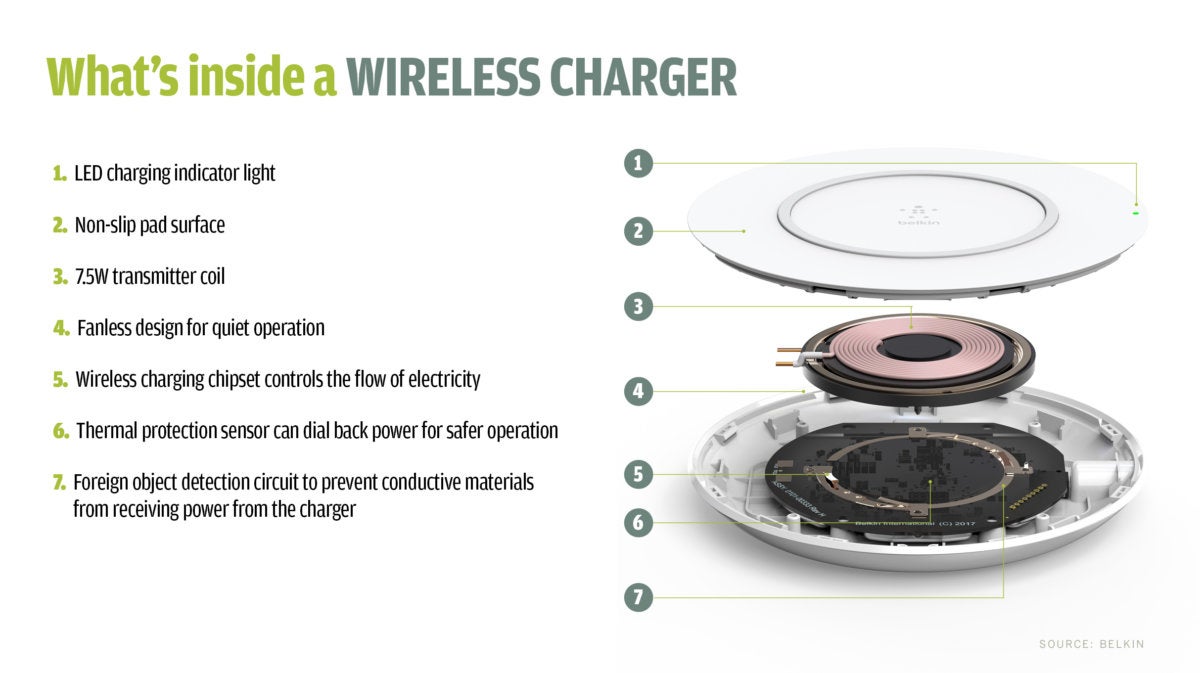

BELKIN/IDG

BELKIN/IDGIn September 2012, the Nokia 920 became the first commercially available smart phone to offer built-in wireless charging capabilities based on the Qi specification.

The wireless charging standards battle

For several years, there were three competing wireless charging standards groups focused on inductive and resonance charging specifications: The Alliance for Wireless Power (A4WP), the Power Matters Alliance (PMA) and the Wireless Power Consortium (WPC). The latter’s 296-member roster includes Apple, Google, Verizon and a veritable who’s who of electronics manufacturers.

The WPC created the most popular of the wireless charging standards – Qi (pronounced “chee”) – which enables inductive or pad-style charging and short-distance (1.5cm or less) electromagnetic resonant inductive charging. The Qi standard is being used by Apple.

APPLE

APPLEThe PMA and its Powermat inductive charging specification found success by piloting its wireless charging technology in coffee shops and airports. Starbucks, for example, began rolling out wireless charging pads in 2014.

With competing standards, support for mobile devices remained fragmented, with most mobile devices needing an adaptive case to enable a wireless charge.

In 2015, the A4WP and the PMA decided to band together to form the AirFuel Alliance, which now has 110 members, including include Dell, Duracell, Samsung and Qualcomm.

PMA/STARBUCKS

PMA/STARBUCKSAs part of the AirFuel Alliance, Duracell Powermat claims it has more than 1,500 charging spots in the U.S., and through Powermat’s partnership PowerKiss, 1,000 charging spots in European airports, hotels and cafes. AirFuel has also announced wireless charging at some McDonald’s restaurants. That, according to Freas, is one way wireless charging could see wider adoption.

AirFuel focuses on electromagnetic resonant and RF

AirFuel has focused on two charging technologies: electromagnetic resonant and radio frequency, which offers the ability to move around a space and still have your mobile device charge.

“We’ve seen clear market indicators that resonant and RF are the way to go. Both technologies offer distinct advantages in terms of spatial freedom, ease of use, and ease of installation – big factors in creating market value and customer satisfaction,” said AirFuel spokesperson Sharen Santoski. “And we believe resonant is the best technology to enable widespread public infrastructure deployment in the near term.”

As a result, Santoski said, a growing number of coffee shops, restaurants and airport have deployed resonant-based wireless charging stations. “Taiwan is investing heavily, as is China,” Santoski said.

AirFuel recently announced a project with the Taoyuan Airport Metro, which is putting Resonant charging in its trains and stations. And furniture maker Order Furniture has created a new line of Resonant-enabled furniture.

“If in every restaurant and coffee shop you have it, then people will be more likely to use it and get a pad to charge at home,” Freas said.

Most of these projects are still just pilot programs, Freas said, adding that consumers and businesses are less likely to want tightly coupled charging and more likely to opt for loosely coupled resonant charging That’s because loosely coupled charging provides more spatial freedom – the ability to simply drop a phone, tablet or laptop on a desktop and have it charge.

WiTricity and wireless charging in vehicles

In July, Dell released a Latitude laptop that incorporates resonant wireless charging from WiTricity, a Watertown, Mass.-based company that licenses technology originally developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The Dell wireless charger offers up to 30W of charging power, so a Latitude laptop will charge at the same rate as it were plugged into a wall outlet.

WITRICITY

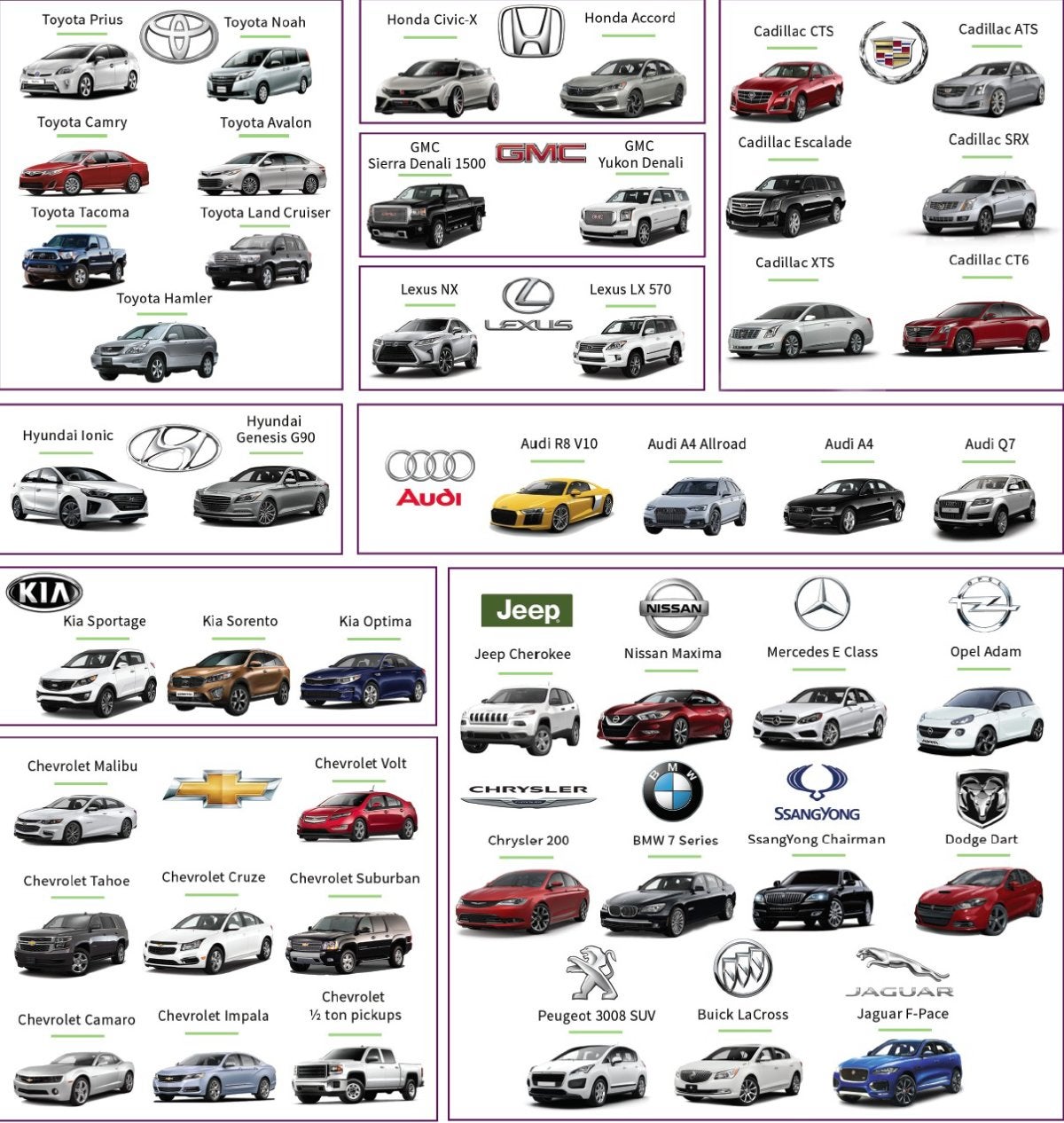

WITRICITYBut WiTricity’s main focus is the auto industry. The company, which is part of the AirFuel Alliance, expects a number of electric car manufacturers to announce wireless charging for their vehicles, according to WiTricity CEO Alex Gruzen.

The company’s electromagnetic resonant technology allows power to transfer at distances of up to about nine inches away from a charging pad. That would allow electric cars to charge just by parking on top of a large charging pad.

For example, Mercedes-Benz this year will roll out S550e plug-in hybrid sedans with the ability to use WiTricity’s technology; the S550e can simply park over a pad and they begin charging even more efficiently than if it were plugged in.

WIRELESS POWER CONSTORTIUM

WIRELESS POWER CONSTORTIUMThe electric vehicle application is tailor-made for electromagnetic resonant charging, Kesler said. That’s because a vehicle doesn’t need a charging cable, and the wireless charging pad delivers electricity more efficiently than a cable. (Wired charging systems use electronics to convert AC to DC and regulate the flow of power, reducing efficiency to about 86%, Kesler said.)

“Our wireless charging can be 93% efficient from end to end – from the wall to what’s being delivered to the battery,” Kesler said.

Wireless charging over distance

This month, Apple surprised some industry watchers by purchasing PowerByProxi, a New Zealand-based company developing loosely-coupled resonant charging technology that’s also based on the Qi specification.

PowerbyProxi was founded in 2007 by entrepreneur Fady Mishriki as a spin-out from the University of Auckland. PowerByProxi has showcased charging boxes and bowls into which multiple devices can be placed and charged at the same time.

The Aukland-based company got its start selling large-scale systems for the construction, telecommunications, defense and agriculture industries. One such product is a wireless control system for wind turbines.

PowerByProxi, a member of the WPC’s Steering Committee, has also miniaturized its technology and placed it into AA rechargeable batteries, eliminating the need to embed the technology directly into devices. The wireless technology takes up about 10% of the AA battery height.

Apple could use PowerByProxi’s technology to expand its use fo wireless charging beyond just smartphones, using it, for instance, to charge TV remote controls, computer peripherals, or any number of devices that require batteries.

While the most visible use of wireless charging technology has been in mobile device charging pads, the technology is also making inroads into everything from warehouse robots to tiny IoT devices that otherwise would need to be wired or powered by replaceable batteries.

Both Ossia and Energous have demonstrated wireless charging beyond 15 feet. Ossia’s charger can send about two watts up to several feet, but that drops off quickly as the distance increases. Even at 30 feet, however, the amount of power that can be transmitted is “meaningful,” according to Ossia CEO Mario Obeidat, alluding to trickle powering devices so as to maintain their charge.

MARK HACHMAN

MARK HACHMAN“Let’s say I’m in an office for eight to 10 hours a day and I’m receiving a half a watt or a watt of power; it’s charging my device all the time,” Obeidat said. “So if it takes five hours to fully charge that devise, that’s fine because you’re there all the time.”

“I’ve used both [Ossia and Energous]; the technology works,” Rob Rueckert, the managing director at Sorenson Capital, a private equity and venture capital firm, said in an earlier interview with Computerworld.

Rueckert believes charging at distance is a more compelling technology than charging pads or even boxes that still require a mobile devices to be relatively tightly connected to a charging source.

POWERBYPROXI

POWERBYPROXIBoth Energous’ WattUp and Ossia’s Cota mobile device charging systems work much like a wireless router, sending radio frequency (RF) signals that can be received by enabled wearables and mobile phones. A small RF antenna in the form of PCB board, an ASIC and software make up the wireless power receivers.

Using a multi-antenna management chip about 4x4mm in size, the Cota power transmitter can be built into a variety of form factors, everything from ceiling tiles to tables, desks, glass, televisions and automobile dashboards.

The transmitter automatically detects Cota-enabled devices and includes a temperature-sensing unit to prevent overheating.

“We call it real wireless power,” Obeidat said. “The difference between our technology and others in market, like Qi, is we can deliver meaningful power remotely. Others require you to place your device on the pad. So, effectively you have to give up the device to charge it.”

Obeidat also claims Cota charging can work through walls, just like a Wi-Fi router.

“Our technology is agnostic. You can envision having a transmitter in room where it powers a smartphone, a tablet or a smart watch, all at the same time,” Obeidat said.

Ossia has been piloting its technology on electronic labels for products on retail shelves. The labels can inform shoppers of product details or sales without requiring workers to place physical signs or change price stickers.

While some have scoffed at the idea of only transmitting a couple of watts of power over distance, investors have taken the idea seriously. For example, Pleasanton, Calif.-based Energous – an AirFuel member – raised about $25 million when it went public in 2014.

Energous’ WattUp charger uses the Bluetooth wireless communication spec. Like Ossia’s Cota technology, the amount of wattage WattUp can send is limited. As a result, Energous is focused on powering small mobile devices rather than laptops or batteries that require higher capacities.

ENERGOUS

ENERGOUSA single WattUp transmitter can charge up to 24 devices, all under software control that enables or disables charging, according to Energous. The maximum amount of power – 4 watts – can only be delivered to four devices simultaneously. As more “authorized” devices enter a room, the charge to each device drops.

One potential obstacle to adoption of wireless charging at distance is that neither Ossia’s nor Energous’ can charge Qi-enabled devices; the technology is proprietary.

Only the beginning

Green believes Qi and Powermat provide a great start, but stresses the technology isn’t completely wireless. “Qi has started the conversation about wireless power. There is an important need to educate consumers about what is possible,” he said.

By starting with a Qi pad charging, users can begin to accept the premise of wireless power and will soon demand a much more flexible, robust solution: power at a distance with the flexibility to use your device while charging.

“One thing is clear: in 2017, we’re not going to see a device offering full-speed wireless charging across a room,” Green said. “There’s two ends of a scale instead, charging at the same speed as a wire but on a charging pad, or perhaps trickle charging very slowly but at a larger distance away.”