advertisement

The long, slow death of commercial Unix

In the 1990s and well into the 2000s, if you had mission-critical applications that required zero downtime, resiliency, failover and…

In the 1990s and well into the 2000s, if you had mission-critical applications that required zero downtime, resiliency, failover and high performance, but didn’t want a mainframe, Unix was your go-to solution.

If your database, ERP, HR, payroll, accounting, and other line-of-business apps weren’t run on a mainframe, chances are they ran on Unix systems from four dominant vendors: Sun Microsystems, HP, IBM and SGI. Each had its own flavor of Unix and its own custom RISC processor. Servers running an x86 chip were at best used for file and print or maybe low-end departmental servers.

Today it’s a x86 and Linux world, with some Windows Server presence. Virtually every supercomputer on the Top 500 list runs some flavor of Linux and an x86 processor. SGI is long gone. Sun lived on for a while through Oracle, but in 2018 Oracle finally gave up. HP Enterprise only ships a few Unix servers a year, primarily as upgrades to existing customers with old systems. Only IBM is still in the game, delivering new systems and advances in its AIX operating system.

advertisement

We aren’t going to dwell on how we got here. Instead, this is a look at where commercial Unix is going, and how and when it will eventually die. (Note: We’re specifically talking about the decline of commercial Unix. Still flourishing are the free and open-source variants such as FreeBSD, which was born out of the Berkeley Software Development (BSD) project at the University of California, Berkeley, and GNU.)

Unix’s slow decline

Unix’s decline is “more of an artifact of the lack of marketing appeal than it is the lack of any presence,” says Joshua Greenbaum, principal analyst with Enterprise Applications Consulting. “No one markets Unix any more, it’s kind of a dead term. It’s still around, it’s just not built around anyone’s strategy for high-end innovation. There is no future, and it’s not because there’s anything innately wrong with it, it’s just that anything innovative is going to the cloud.”

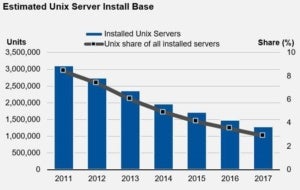

“The UNIX market is in inexorable decline,” says Daniel Bowers, research director for infrastructure and operations at Gartner. “Only 1 in 85 servers deployed this year uses Solaris, HP-UX, or AIX. Most applications on Unix that can be easily ported to Linux or Windows have actually already been moved.”

advertisement

Most of what remains on Unix today are customized, mission-critical workloads in fields such as financial services and healthcare. Because those apps are expensive and risky to migrate or rewrite, Bowers expects a long-tail decline in Unix that might last 20 years. “As a viable operating system, it’s got at least 10 years because there’s this long tail. Even 20 years from now, people will still want to run it,” he says.

GARTNER

GARTNER

Gartner doesn’t track install base, just new sales, and the trend is down. In Q1 of 2014, Unix sales totaled $1.6 billion. By Q1 of 2018, sales were at $593 million. In terms of units, Unix sales are low, but they are almost always in the form of high-end, heavily decked-out servers that are much larger than your typical two-socket x86 server.

advertisement

IBM the last UNIX man standing

It’s remarkable how tight-lipped people are over the state of Unix. Oracle and HPE declined to comment, as did several IBM customers. IBM is still in the game, but Bowers notes, “I see IBM investing $34 billion in Red Hat, but I don’t see IBM investing $34 billion in AIX.”

Steve Sibley, vice president of cognitive systems offerings at IBM, acknowledges the obvious but says IBM will still have a substantial number of clients on AIX in ten years, with the majority of clients being large Fortune 500 clients. He adds that there will also be a stable number of midrange customers in some ways “because they don’t want to spend the investment to get off AIX.”

Rob McNelly, senior AIX solutions architect at Meridian IT, a services provider and heavy AIX user, says there is an 80/20 rule for new applications for AIX: 80% of customers don’t grow their AIX footprint, but 20% stays and expands in AIX.

“Because 20% is the larger enterprise systems, it is a very big segment. In healthcare, many stable tier 1 production environments continue to invest and enjoy the stability and security of AIX. Established and embedded ERP systems do likewise at all layers,” McNelly says.

Many new applications pursue Linux, which causes some migration off of AIX, while static, non-changing environments just stay in stable AIX, he adds. “Some applications are going to Linux, but most of the low-end stuff already moved. Think of the mainframe; existing users stay because it has great value, but not many new customers are migrating to the mainframe.”

Finance, healthcare and big manufacturing are the primary industries sticking with Unix, Bowers says. Banking firms are often able to afford these big systems, while healthcare has strict regulatory requirements that pressure companies to stay put on the Unix platform.

“No one buys a platform for the platform,” McNelly says. “They buy an application. As long as application support remains for some key platforms, it’s hard to beat the value of AIX on [IBM Power Systems]. Many times after companies do some analysis, [and consider] the current stability and the migration effort, [it] makes no sense to move out of something that’s perfectly functional and supported and has a strong roadmap into the future.”

The biggest complaint Bowers hears about Linux is not the OS itself but the hardware it runs on. Many Unix systems have something called hard partitioning, which is like virtual machines, but it sets up physically separated partitions on the system. Hard partitioning has multiple benefits. For example, Bowers notes that in some cases, enterprise software vendors (Oracle is one example) will give you a discount if you use hard partitioning. This is a hardware solution only Unix systems offer today.

Unix is the new mainframe

While Unix is in decline and there is only one commercial vendor left, the other two popular flavors will hang around for a while. Oracle may have ended development of Solaris but has committed to support Solaris until 2034. HP Enterprise says it will support its various HP-UX servers for five years after their obsolescence date, which varies. SGI’s IRIX has been off the market and out of support since 2006.

Sibley says the trend IBM is seeing is clients less focused on moving off AIX and more focused on how to extend and migrate going forward. “The vast majority of customers are extending what they are doing with AIX and not looking to get off,” he says.

The primary reason people move off AIX is they are worried there won’t be the skills to support it in the future, because customers believe AIX is dying. “That’s what gets people’s attention. As long as they have confidence we will be around a long time, and we have new releases every year, then there’s no reason to get off,” Sibley says.

So Unix will live on at least in the form of AIX due to IBM’s commitment, even as the others fade out in the coming decades. No one expects a supernova-like implosion. Just a very slow, long fade.

“Unix will never die. There is no research that is trying to come up with a new operating system to replace Unix or Linux,” Greenbaum says. “It won’t die the way mainframe systems have not died. They are still in use. But this stuff fades out of view because it loses strategic value.”

“By 2020, Unix will represent 3% of total server revenue, down from 8% today,” Bowers says. “There’s not going to be a rush for the exit. Unix will fade away.”

In the end, Unix’s greatest success likely won’t be as an enterprise server but as an option for consumer products. Apple’s MacOS and iOS are both derived from FreeBSD – and that installed base isn’t going anywhere.