advertisement

What is a botnet? And why they aren’t going away anytime soon

A botnet is a collection of any type of internet-connected device that an attacker has compromised. Botnets act as a…

A botnet is a collection of any type of internet-connected device that an attacker has compromised. Botnets act as a force multiplier for individual attackers, cyber-criminal groups and nation-states looking to disrupt or break into their targets’ systems. Commonly used in distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, botnets can also take advantage of their collective computing power to send large volumes of spam, steal credentials at scale, or spy on people and organizations.

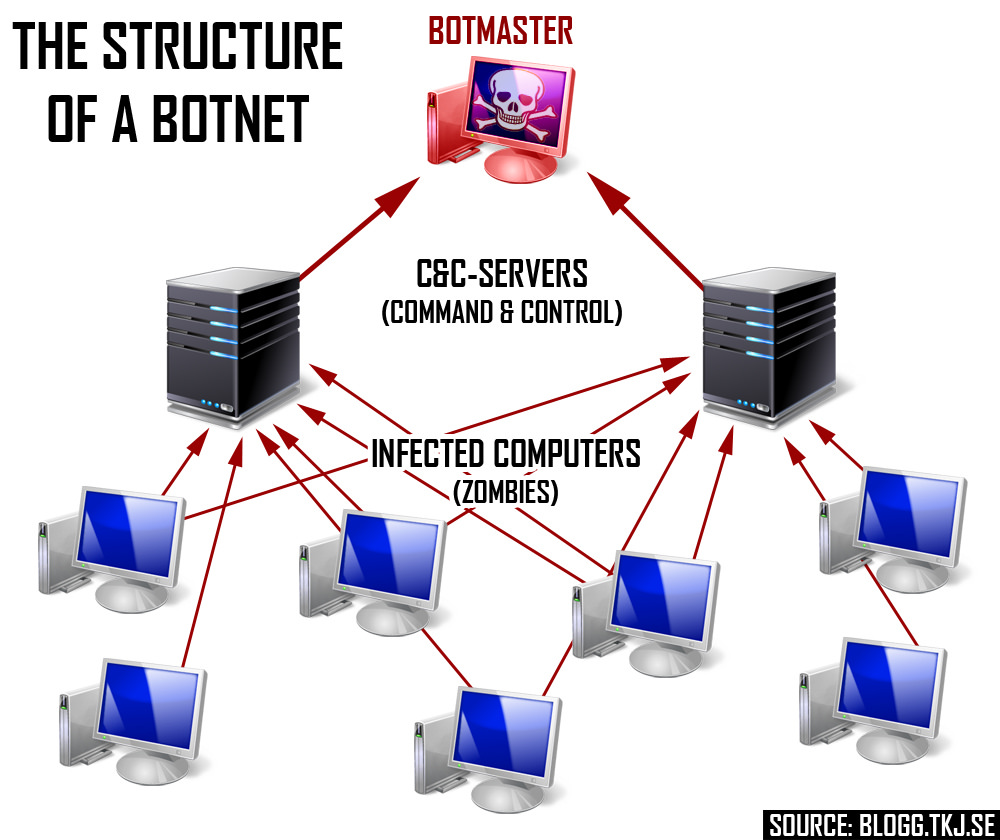

Malicious actors build botnets by infecting connected devices with malware and then managing them using a command and control server. Once an attacker has compromised a device on a specific network, all the vulnerable devices on that network are at risk of being infected.

A botnet attack can be devastating. In 2016, the Mirai botnet shut down major swathes of the internet, including Twitter, Netflix, CNN and other major sites, as well as major Russian banks and the entire country of Liberia. The botnet took advantage of unsecured internet of things (IoT) devices such as security cameras, installing malware that then attacked the DYN servers that route internet traffic.

advertisement

The industry woke up, and device manufacturers, regulators, telecom companies and internet infrastructure providers worked together to isolate compromised devices, take them down or patch them, and make sure that a botnet like could never be built again.

Just kidding. None of that happened. Instead, the botnets just keep coming.

Even the Mirai botnet is still up and running. According to a report released by Fortinet in August 2018, Mirai was one of the most active botnets in the second quarter of this year.

advertisement

Since the release of its source code two years ago, Mirai botnets have even added new features, including the ability to turn infected devices into swarms of malware proxies and cryptominers. They’ve also continued to add exploits targeting both known and unknown vulnerabilities, according to Fortinet.

In fact, cryptomining is showing up as a significant change across the botnet universe, says Tony Giandomenico, Fortinet’s senior security strategist and researcher. It allows attackers to use the victim’s computer hardware and electricity to earn Bitcoin, Monero and other cryptocurrencies. “That’s the biggest thing that we’ve been experiencing over the past few months,” he says. “The bad guys are experimenting with how they can use IoT botnets to make money.”

Mirai is just the start. In fall 2017, Check Point researchers said they discovered a new botnet, variously known as “IoTroop” and “Reaper,” that’s compromising IoT devices at an even faster pace than Mirai did. It has the potential to take down the entire internet once the owners put it to work.

advertisement

Mirai infected vulnerable devices that used default user names and passwords. Reaper goes beyond that, targeting at least nine different vulnerabilities from nearly a dozen different device makers, including major players like D-Link, Netgear and Linksys. It’s also flexible, in that attackers can easily update the botnet code to make it more damaging.

According to research by Recorded Future, Reaper was used in attacks on European banks this year, including ABN Amro, Rabobank and Ing.

Why we can’t stop botnets

The challenges to shutting botnets down include the widespread availability and ongoing purchases of insecure devices, the near impossibility of simply locking infected machines out of the internet, and difficulty tracking down and prosecuting the botnet creators. When consumers go into a store to buy a security camera or other connected device, they look at features, they look for recognizable brands, and, most importantly, they look at the price.

Security is rarely a top consideration. “Because [IoT devices are] so cheap, the likelihood of there being a good maintenance plan and fast updates is low,” says Ryan Spanier, director of research at Kudelski Security.

Meanwhile, as people continue to buy low-cost, insecure devices, the number of vulnerable end points just keeps going up. Research firm IHS Markit estimates that the total number of connected devices will rise from nearly 27 billion in 2017 to 125 billion in 2030.

There’s not much motivation for manufacturers to change, Spanier says. Most manufacturers face no consequences at all for selling insecure devices. “Though that’s starting to change in the past year,” he says. “The US government has fined a couple of manufacturers.”

For example, the FTC sued D-Link in 2017 for selling routers and IP cameras full of well-known and preventable security flaws such as hard-coded login credentials. However, a federal judge dismissed half of the FTC’s complaints because the FTC couldn’t identify any specific instances where consumers were actually harmed.

How to detect botnets: Target traffic

Botnets are typically controlled by a central command server. In theory, taking down that server and then following the traffic back to the infected devices to clean them up and secure them should be a straightforward job, but it’s anything but easy.

When the botnet is so big that it impacts the internet, the ISPs might band together to figure out what’s going on and curb the traffic. That was the case with the Mirai botnet, says Spanier. “When it’s smaller, something like spam, I don’t see the ISPs caring so much,” he says. “Some ISPs, especially for home users, have ways to alert their users, but it’s such a small scale that it’s not going to affect a botnet. It’s also really hard to detect botnet traffic. Mirai was easy because of how it was spreading, and security researchers were sharing information as fast as possible.”

Compliance and privacy issues are also involved, says Jason Brvenik, CTO at NSS Labs, Inc., as well as operational aspects. A consumer might have several devices on their network sharing a single connection, while an enterprise might have thousands or more. “There’s no way to isolate the thing that’s impacted,” Brvenik says.

Botnets will try to disguise their origins. For example, Akamai has been tracking a botnet that has IP addresses associated with Fortune 100 companies — addresses that Akamai suspects are probably spoofed.

Some security firms are trying to work with infrastructure providers to identify the infected devices. “We work with the Comcasts, the Verizons, all the ISPs in the world, and tell them that these machines are talking to our sink hole and they have to find all the owners of those devices and remediate them,” says Adam Meyers, VP of intelligence at CrowdStrike, Inc.

That can involve millions of devices, where someone has to go out and install patches. Often, there’s no remote upgrade option. Many security cameras and other connected sensors are in remote locations. “It’s a huge challenge to fix those things,” Meyers says.

Plus, some devices might no longer be supported, or might be built in such a way that patching them is not even possible. The devices are usually still doing the jobs even after they’re infected, so the owners aren’t particularly motivated to throw them out and get new ones. “The quality of video doesn’t go down so much that they need to replace it,” Meyers says.

Often, the owners of the devices never find out that they’ve been infected and are part of a botnet. “Consumers have no security controls to monitor botnet activity on their personal networks,” says Chris Morales, head of security analytics at Vectra Networks, Inc.

Enterprises have more tools at their disposal, but spotting botnets is not usually a top priority, says Morales. “Security teams prioritize attacks targeting their own resources rather than attacks emanating from their network to external targets,” he says.

Device manufacturers who discover a flaw in their IoT devices that they can’t patch may, if sufficiently motivated, do a recall, but even then, it might not have much of an effect. “Very few people get a recall done unless there’s a safety issue, even if there’s a notice,” says NSS Labs’ Brvenik. “If there’s a security alert on your security camera on your driveway, and you get a notice, you might think, ‘So what, they can see my driveway?'”

How to prevent botnet attacks

The Council to Secure the Digital Economy (CSDE), in cooperation with the Information Technology Industry Council, USTelecom and other organizations, recently released a very comprehensive guide to defending enterprises against botnets. Here are the top recommendations.

Update, update, update

Botnets use unpatched vulnerabilities to spread from machine to machine so that they can cause maximum damage in an enterprise. The first line of defense should be to keep all systems updated. The CSDE recommends that enterprises install updates as soon as they become available, and automatic updates are preferable.

Some enterprises prefer to delay updates until they’ve had time to check for compatibility and other problems. That can result in significant delays, while some systems may be completely forgotten about and never even make it to the update list.

Enterprises that don’t use automatic updates might want to reconsider their policies. “Vendors are getting good at testing for stability and functionality,” says Craig Williams, security outreach manager for Talos at Cisco Systems, Inc.

Cisco is one of the founding partners of the CSDE, and contributed to the anti-botnet guide. “The risk that used to be there has been diminished,” he says.

It’s not just applications and operating systems that need automatic updates. “Make sure that your hardware devices are set to update automatically as well,” he says.

Legacy products, both hardware and software, may no longer be updated, and the anti-botnet guide recommends that enterprises discontinue their use. Vendors are also extremely unlikely to provide support for pirated products.

Lock down access

The guide recommends that enterprises deploy multi-factor and risk-based authentication, least privilege, and other best practices for access controls. After infecting one machine, botnets also spread by leveraging credentials, says Williams. By locking down access, the botnets can be contained in one place, where they’re do less damage and are easier to eradicate.

One of the most effective steps that companies can take is to use physical keys for authentication. Google, for example, began requiring all its employees to use physical security keys in 2017. Since then, not a single employee’s work account has been phished, according to the guide.

“Unfortunately, a lot of business can’t afford that,” says Williams.In addition to the upfront costs of the technology, the risks that employees will lose keys are high.

Smartphone-based second-factor authentication helps bridge that gap. According to Wiliams, this is cost effective and adds a significant layer of security. “Attackers would have to physically compromise a person’s phone,” he says. “It’s possible to get code execution on the phone to intercept an SMS, but those types of issues are extraordinarily rare.”

Don’t go it alone

The anti-bot guide recommends several areas in which enterprises can benefit by looking to external partners for help. For example, there are many channels in which enterprises can share threat information, such as CERTs, industry groups, government and law enforcement information sharing activities, and via vendor-sponsored platforms.

Another area in which a company shouldn’t rely solely on its own internal resources is in protecting against DDoS attacks. “Generally speaking, with DDoS, you want to stop it as far away from you as you can,” says Williams. “Lots of people assume that if you have an intrusion protection system or a firewall, it will stop a DDoS attack. That’s not actually the case.”

Deepen your defenses

It’s no longer enough to secure the perimeter, or endpoint devices. “Attackers are really creative these days,” says Williams. “They can add stress to your network from a number of different vendors.” Having multiple defensive systems in place is like having several locks on a door, he says. If the attackers figure out how to get past one lock, the other locks will stop them.

The anti-botnet guide recommends that enterprises consider using advanced analytics to secure users, data, and networks, to ensure that security controls are correctly set, and to use network segmentation and network architectures that securely manage traffic flows. For example, IoT devices should be on a separate, isolated part of the network, says Williams.

The Mirai botnet, for example, took advantage of insecure connected devices. “When you have IoT devices that can’t be patched on the same network as the rest of the enterprise, it adds a significant level of risk that doesn’t need to be there,” he says.

Botnet dragnets have some success

In late 2017, the Andromeda botnet was taken down by the FBI working together with law enforcement in Europe. Over the previous six months, the botnet was detected on blocked on an average of more than a million machines every month.

According to Fortinet, however, the Andromeda botnet was still active in the second quarter of this year — in fact, it was the second biggest by volume, infecting devices on more than 20 percent of companies. It’s hard to take them down, says Fortinet’s Giandomenico. “Who is responsible? Is it the government that’s responsible for going out there and cleaning it up?”

And it’s about to get even harder, he adds.

With a botnet controlled by central servers, once the servers are removed, the botnet becomes inactive. But botnets are starting to operate in mesh fashion, with peer-to-peer communications that can make the botnets extremely resilient, Giandomenico says. It’s not just a theoretical problem, he adds, with a few botnets already known to be running in decentralized, mesh mode. “It is a slow but growing trend,” he says. “Some of the more famous ones are Hajime, Hide N’ Seek and TheMoon.”

In addition to taking down command and control servers, authorities can also attack botnets by going after their customers. DDoS-as-a-service providers, for example, use botnets to launch massive attacks on behalf of anyone with some spare cash in their PayPal or Bitcoin wallets.

This spring, authorities from the UK and the Netherlands teamed up in Operation Power Off to take down one of the largest DDoS-as-a-service operators, webstresser.org, and arrested platform admins located in the UK, Croatia, Canada and Serbia. The service had 136,000 registered users and was responsible for 4 million attacks, according to Europol, with services running for as little as 15 euros a month.

Webstresser.org is only one of many such sites, according to a report Akamai released this summer. So far, there’s been no sign of a drop in DDoS attacks as a result.

Authorities also go after the creators who build the botnets in the first place, according to Adam Meyers, VP of intelligence at CrowdStrike, Inc. For example, in 2017, authorities arrested Peter “Severa” Levashov, the hacker behind the Waledac and Kelihos spam botnets. “He was arrested while on vacation in Spain,” Meyers says. “It required coordination between the Department of Justice, the FBI, and Spanish police. There was a lot of international cooperation. Plus, there was technical expertise required to disrupt the botnet, which involved us sending some technical experts to Alaska to help the FBI with the takedown.”

Shutting down a botnet’s servers isn’t enough to solve the problem if the creators are still out there. “With Kelihos, that was disrupted five times or so,” Meyers says. “But because the author of that botnet was not apprehended, he was able to spin it back up, in some cases within hours of the disruption. After a couple of times, people realized that this wasn’t going to go anywhere until we take this guy off the street.”

In the case of the Andromeda botnet, even arresting the creator wasn’t enough. It took a massive cooperative effort by international law enforcement agencies and technology and security vendors to take down the network, which involved 464 botnets, 1,214 command-and-control domains, and 80 malware families.

Andromeda has been around since 2011, with ready-to-go botnet kits sold on the dark web, also known as Gamarue and Wauchos. It was responsible for infecting more than 1.1 million systems per month. The law enforcement groups began working to take them down in 2015, says Jean-Ian Boutin, senior malware researcher at ESET, LLC, one of the groups working on the takedown. “This type of operation takes time,” he says. During that time, security teams analyzed thousands of Andromeda samples. “Based on this, we believe that this operation led to the disruption of all current Andromeda botnets.”

However, not only is Andromeda still there, and still big, but the creator who was arrested in the takedown is also back on the street. Sergei Yarets was released this summer by Belarus authorities after six months in prison and a relatively small fine — the equivalent of about $5,500.

“This case is another example of a double standard toward prosecuting cybercriminals in post-Soviet countries, where they treat their own cybercriminals differently, allowing them to avoid fair punishment and then using them in the interests of the state, neutralizing the efforts of the international community to combat cybercrimes,” says Alexandr Solad, a researcher with Recorded Future, in a report in August 2018.

A long way from a permanent solution to botnets

Even arresting the hackers in the first place is difficult. The problem is that there haven’t been that many arrests, Meyers says. “[Russian hacker Evgeniy] Bogachev was fingered in June 2014 in the Gameover Zeus attacks, and he’s still at large in Russia someplace,” he says. “A lot of these guys don’t have to worry about arrests. If they work in Russia, and don’t target Russian systems, they can pretty much operate with impunity.” Bogachev is currently on the FBI’s Cyber’s most wanted list.

Permanently solving the botnet problem requires a global solution to cybercrime, on top of the technical challenges, says Daniel Miessler, director of advisory services at IOActive, Inc. That’s not happening in the foreseeable future. “Botnets are an emergent malady that exist because of the vulnerabilities and incentives that exist within society,” he says. “Until we fix those, we should expect botnets and other emergent intersections between malice and vulnerability, to be permanent co-passengers.”

In addition to creating a common, worldwide cybercrime enforcement system, there also needs to be standard regulations for manufacturers, requiring a certain level of minimal security in IoT devices. “Any regulation must also apply to all manufacturers, as many markets tend to be flooded with very cheap devices produced in regions where internet laws are very lax or non-existent,” says Rod Soto, director of security research at Jask, an AI cybersecurity startup.

It’s hard to imagine all the world’s nations and affected industries coming together and agreeing on a common approach, and then enforcing it, says Igal Zeifman, product evangelist at Incapsula, Inc. “All initiatives to combat the growth of botnets through industry standards and legislation will likely continue to occur only on a regional or country level,” he says.

That means that even if individual countries can slow down the growth of botnets in their regions, there will still be plenty of other places where they can grow. “Considering the global nature of the internet, this means that botnet attacks will continue to pose a threat to the digital businesses and the online community for many years to come,” Zeifman says.